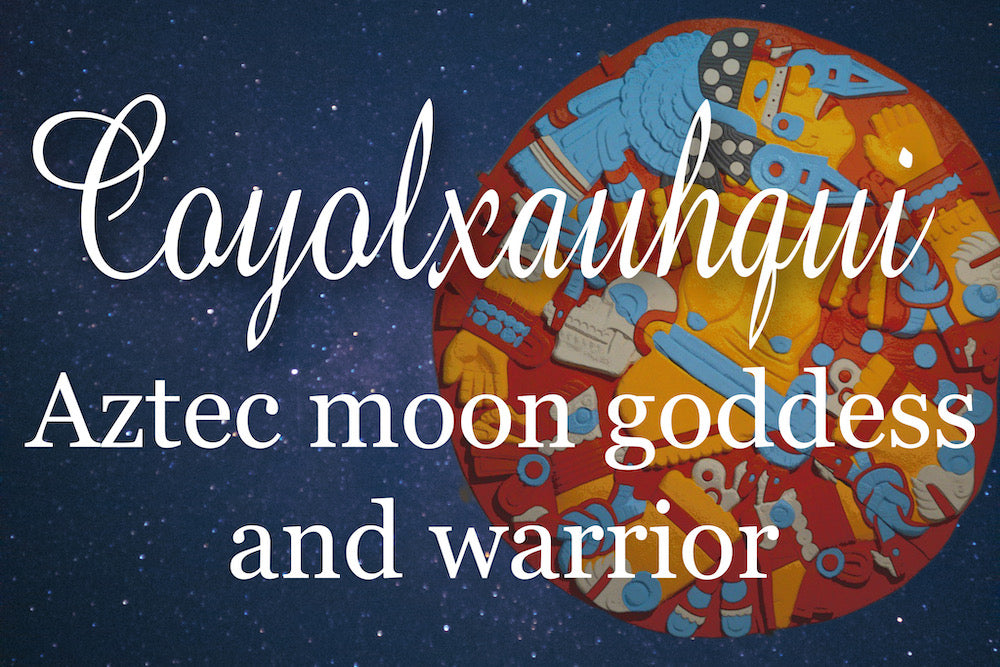

In the early hours of February 21st of 1978, in the heart of Mexico City, a team of workers found a round monolith completely carved on its upper face. In the spectacular circular stone sculpture, the Mexica/Aztec lunar deity was represented: Coyolxauhqui a magnificent female warrior who met her brother for battle to be defeated and later beheaded.

This massive carved stone, weighting 8 tons with 10.5 ft in diameter, at first sight presents the dynamic figure of a woman who appears to be dancing. However, upon closer examination, it becomes clear that the image presented is that of a powerful warrior’s demise with her head, arms, and legs dismembered. This unique piece depicts the importance of her defeat by Huitzilopochtli in Aztec/Mexica religion and has become a symbol for Mexican national identity.

Who is Coyolxauhqui?

According to Mexica/Aztec mythology, Coyolxauhqui, whose name in Nahuatl means "the one adorned with bells," was the leader of her 400 brothers, known as the Centzon Huitznahua (the 'Four Hundred Huitznahua' who represented the stars of the southern sky). She was the daughter of Coatlicue, "the one with the serpent skirt," goddess of the earth and fertility, and the sister of Huitzilopochtli, "the left-handed or southern hummingbird," the Mexica/Aztec god of war and main deity who would lead the Mexica people to Tenochtitlan, the promised land.

The myth of Coyolxauhqui is closely related to that of Huitzilopochtli’s and it recounts the story of his birth, tied with Coyolxauhqui’s demise. It takes place during the migration of the Aztec people from Aztlán to Tenochtitlán, the ancestral promised land, what is now Mexico City. This important myth recalls a time during their migration when they briefly settled at the sacred mountain of Coatepec, the “hill of the snake,” located next to the town of Tula (what is now the state of Hidalgo).

The myth goes like this:

Coyolxauhqui's demise at the hands of Huitzilopochtli is said to symbolize the daily victory of the sun (one of Huitzilopochtli’s associations) over the moon and stars and/or light over darkness. However, other scholars suggests that this myth intended to narrate the tensions between fractions who wanted to settle at Coatepec versus those who wanted to continue their search for Tenochtitlán. Others also suggest that with this myth, the Aztecs justified the violence used to conquer and demand tribute from other Mesoamerican peoples.

The myth of Coyolxauhqui and Huitzilopochtli’s birth, was so significant for the Mexica/Aztec people that, commemorating the victory of Huitzilopochtli, the Mexica carved this large stone disk which sat at the base of the stairs of the Huēyi Teōcalli, or the Templo Mayor. They recreated the birth of Huitzilopochtli in ceremonies performed in the precinct of Tenochtitlán, including the demise of Coyolxauhqui as an important part of these celebrations.

Currently exhibited in room 4 of the Museo del Templo Mayor, this beautiful piece is as imposing as it is revealing of what Mexica/Aztec culture was like before the arrival of the Spanish. Although the pre-Hispanic piece was already mentioned in the chronicles of Spanish missionaries as part of the Mexica culture, it was until 44 years ago, when it was discovered, that it has been the subject of multiple research and conversations about Mexica deities. Even more importantly, the finding of this monolith is what led to the excavation of the Tempo Mayor de Tenochtitlán, located in the zocalo of Mexico City, and now visible to those who visit.

The image of Coyolxauhqui (the same as that of her mother, Coatlicue) today has been used by Chicana feminist scholars (First developed by Gloria Anzaldúa) to speak about the ongoing and lifelong process of healing from traumatic events which fragment, dismember, or wound the self. The concept has been used in various contexts where healing is necessary such as that of identity, cultural, educational, and even historical, making Coyolxauhqui as important and relevant as it was centuries ago.

So, what do you think? Have you ever seen this carved stone in Templo Mayor? What about pictures of it? Were you familiar with the myth of Coyolxauhqui or any other part of Aztec/Mexica mythology? What do you think about it? We would love to hear from you!

3 comments

LOS GLOBOS RUMBÁ 🎈🎈🎈🎈🎈🎈🎈🎈

🌴SI COMO NO🌴LA FANTASIA ES BUENA CON GANAS OK.😃🪘🗽🌴🎈Y RÙMBÁLĒ🪘

Ramon Torres

The year was 1979 when I first read about the accidental Discovery of the The Coyolxauhqui Aztec Moon Goddes monolithic stone sculpture.

Raised in East Los Angeles and and one of many Chicano activists of the time, my focus was on promoting our indigenous cultural roots and Heritage as well as equal justțy,and educational opportunities for higher education and government jobs which were very difficult to obtain at the time and called for the organization of the first Historical High School Walkouts in the U.S. Public Demonstrations and Vietnam Moratorium

As an Anthropolgy, and Chicano studies major and minor studies student i was in volved With the EOP and Mecha student organization and helped create the first official Día de La Raza event and produced an art exhibit at the Cal Sate UniversityLong Beach, school of Art gallery exhibit “10,000 years of Chicano art incorporating on loan artifacts from the Museum of Natural l History, painting from Goez Art Gallery East Los Angeles

In 1979 at an exhibit at Goez Art gallery in in East Lois Angelesni met Mexican artist and sculptor Carlos Venegas. I briefly talked to him and asked if he would come to my house then in the City of Rivers at a house with horse property and a 1/2 Acre backyard to come and see the low relief carving I was making of the Lord Pacal Temple of the Inscriptions Palenque tomb cover releif called by many today the Astronaught.

From this visits and sgterconversation I presented to Carlos Vinegas after we talked about his sculpting experience and adventures in reproducing, and working with original Mayan monolithic Stelae’s in the jungles of Mexico hidden undiscovered archaeological sites found by Chicleros and protected by Mexican Gorilla jungle fighters,

I was convinced he was the perfect person to work with me on being the ffirst to reproduce a facsimile exact reproduction of the Aztec moon goddess recently discovered monolith Coyolxauhqui.

And so begin our partnership in the creation of An exact facsimile reproduction, sculpted by Carlos Venegas and assisted by apprentice, Ramon Torres in his backyard in in the city ot Pico Rivera summer of 1980.

The scripture was finished in 1982 made

out a of 2000 pounds of plaster of Paris.

. A community celebration in the backyard of Ramon Torres house was done that summer honoring the finishing of a major work of art.

I then sold and made a 10,000 pound cement reproduction taken from a fiberglass mold we made of fiberglass and sold to the County of Los Angeles beautification and improvement projects. Public works in 1983, and installed as a historical landmark in the city, of Los Angeles community of city Terrace on the corner of Miller Street and City Terrace Dr., Los Angeles,, CA as in October 12, 1985 with a dedication ceremony.

A 40 year anniversary Ceremony is being organized

For next year October 2025,

Chris

I saw the stone when it was on display at Wichita State University decades ago. I also taught the legend to my Spanish students.