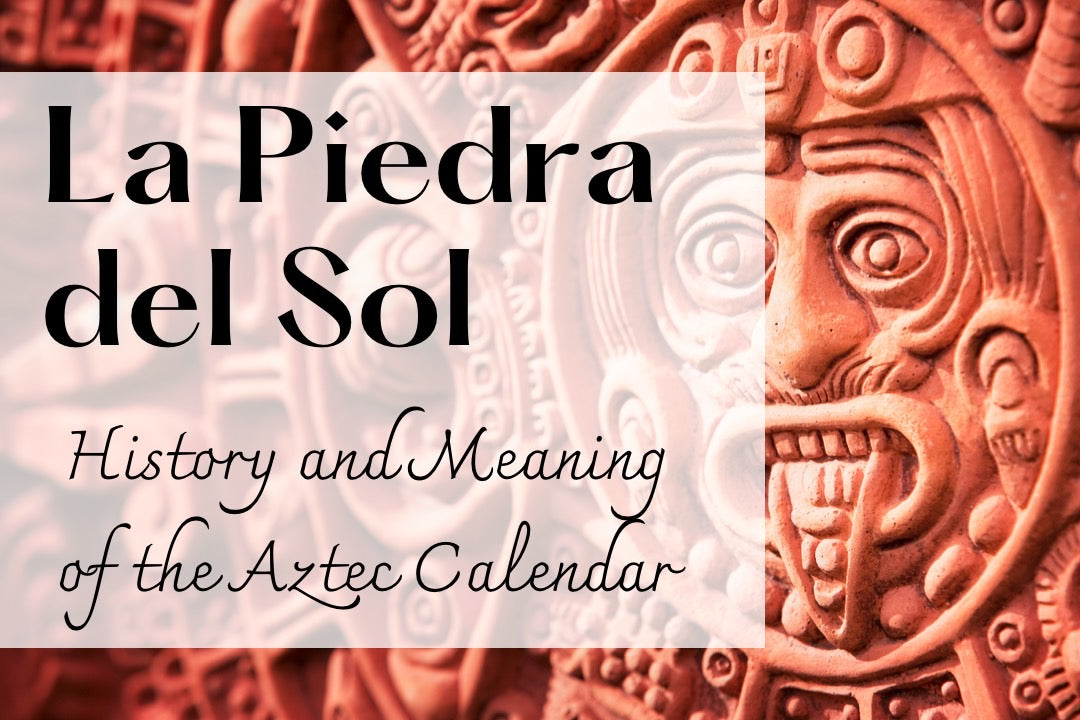

Commonly known as the Aztec Calendar, La Piedra del Sol (Stone of the Sun) is one of the most representative pieces of the Mexica culture. Although, not really a calendar as we know it today, this iconic monument synthesizes the astronomical knowledge that the Mexica society developed and the order under which they lived.

Impressive in size!

This monolith is an unfinished piece, which has been confused with a calendar because in its circles we can find a clear disposition of time, movement of the stars, and cycles of months, as conceived by the Mexica culture. Essentially, for the Mexica, this stone commemorates the time created and destroyed by the gods.

La Piedra del Sol dates from the time of Tlatoani Axayácatl, the sixth Mexica ruler. It is estimated that it was carved in 1479 and it is known that it occupied a prominent place in the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlán.

It is an impressive block of olivine volcanic basalt that measures 3.60 meters (11.8 ft) in diameter and is 122 centimeters (4 ft) thick. The total weight of the monolith is around 25 tons! It is believed that the stone comes from either the Pedregal de San Ángel or Xochimilco area, so it had to be transported from the south of Mexico City to the Templo Mayor in the central area 12 to 22 kilometers (7.5-13.5 miles).

This huge monolith remained in place until the arrival of the Spanish and the defeat of the Mexica empire, when in 1559 the stone was buried facing down, since the Spanish believed that the stone had been the work of the devil and exerted bad influence on the (indigenous) townspeople—as it happened with many other Mexica cultural and religious symbols.

It remained underground until December 17, 1790 when it returned to light by accident. During paving and leveling works that were carried out in the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City (what is now the Zócalo of the city), La Piedra del Sol was found at a depth of 1.3 ft from the ground, practically emerging by itself!

After its uncovering, it was moved to the outside of the Templo Mayor, where it was kept out in the open, with the relief facing out/upwards for many years. There, it could be admired by all, but it also had a huge deterioration from the elements and the people who would throw food scraps and trash at it, and even soldiers that would play bullseye, shooting at the center of the stone.

It was not until September 1887 when it was transferred to a closed, protected location: the Museo Nacional (National Museum) located on Calle de la Moneda, where it occupied the central place of the Monolith Gallery for 77 years.

In 1964 the sculpture left its place on Calle de la Moneda and was transferred to the Bosque de Chapultepec on a 16-meter platform, in a journey of one hour and 15 minutes, to be installed in the Museo Nacional de Antropología (National Museum of Anthropology), where it currently occupies the stellar place in the Sala Mexica.

So what is the Aztec Calendar if not a calendar?

Although La Piedra del Sol symbolizes the conception of time, it did not function as a calendar for the Mexica. The monolith is arranged with a succession of concentric rings that have elements related to time, for example, it describes the duration of the months, the number of days that a year contained, and the duration of the Mexica centuries.

In the center of the monolith is carved the face of Tonatiuh, known by the Aztecs as the fifth solar god, who was the leader of the sky. This warrior sun has his tongue represented by a knife, a symbol of the human sacrifice that the solar god demanded to feed and be reborn each day after his nocturnal journey through the underworld.

Going outwards, the second main ring is formed by four cross symbols that represent the end of the four preceding ages. They are linked with the four elements of Nature: earth, water, air, and fire. Or, in another reading, they also represent the four cardinal points. Together they represent the fifth, current age of Nahui Ollin Tonatiuh.

The third circle is the ring of days and we can see carved 20 figures that symbolize the 20 days of the Mexica calendar. The following rings, from the 4th to the 7th, are the rings of the years. In the outer circle, called the Milky Way because it represents the heavens, two flaming serpents meet forming a final circle, with their heads down and spitting, like two faces that represent day and night, duality. These are related to time and are called "Fire Serpents (Xihuacoatl)”

Meaning of the Aztec Calendar

The Aztecs considered the sun god as one of their main deities. They believed that they were chosen for their subsistence. For this reason, the Aztecs had to ensure that the sun fulfilled its process of rising at dawn and hiding at sunset through their way of life, which sometimes included rituals offering human sacrifices.

Likewise, war and harvests had to be carried out at certain times of the year. In this way, the Piedra del Sol for the Aztec culture, ensured that the fulfillment of the future followed a constant and stable order.

There are several interpretations about the function of the calendar because, despite being related to the distribution of time, it is also believed that the stone had other additional uses, such as a horizontal platform in which sacrifices took place. It is also believed that the main function of the calendar was to help specify the times of the harvests and the rituals with which all the gods were honored.

The Aztecs left carved through the centuries their way of understanding the world. With the iconic Aztec Calendar, people all over the world recognize the significance of our history and people.

-

Tell us, have you ever seen this impressive monolith? What else do you know about it? Is there any other historical fact you would like for us to highlight? We would love to hear from you and read all of your comments below!

Don’t forget to to subscribe to our newsletter if you would like to receive more articles like this one and to check out our shop to get the latest from Mexico to your doorstep!

4 comments

Kayla johnson

Yes it’s Aztec history it left craved through the centuries.

Travis

It is Aztec history

It is a carving of the sun god

It simbilises the consequences of time

Travis

It is Aztec history

It is a carving of the sun god

It simbilises the consequences of time

Bel-Ami Margoles

Yes, when I was a child and shortly after it was installed in the Museo Nacional de Antropología.

My mother was a docent at the Natural history museum in Los Angeles and she spoke Spanish. We got to go down in basements and see things that were being excavated under Mexico City, as well as visiting outdoor excavations in Mexico. I loved it. I remember being wowed by a diorama (or maybe it was a painting?) of Tenochtitlan- a beautiful city sitting among floating gardens!